Shortly after 11.pm on the night of 21 December 1869, Thomas O’ Brien, the stationmaster on Ewell West Railway Station prepared to turn the gas lights off as he awaited the last train of the night – the 10.40 pm from Waterloo. A single passenger alighted who Mr O’ Brien would later describe as wearing a ‘villainous expression of countenance’. He was so alarmed at the man’s appearance and odd manner he ordered him from his pristine new station.

The man, Thomas Huggett, had no intention of hanging around as he had murder in his heart and he set off, following the course of the River Hogsmill, to the gunpowder mills owned by Sharp & Company and that were situated by the river in the areas leading up to what is now Ewell Court Park. He knew the mills well as he had delivered and collected from there in the past. Breaking into an outhouse he stole 25lb of gunpowder and feeling in his pocket to ensure he also had his knife he headed back towards Ewell Village and the house in West Street where his former lover, Lizzie Richardson, was now living.

Huggett worked in a warehouse at Rotherhithe and had been living with Lizzie Richardson for six months after she had left her husband for him. They had never married and the relationship had quickly broken down and Lizzie had moved away from him to live with her sister Eliza and her husband George Spooner and was acting as housekeeper as Eliza had been ill for some months. Also living in the cottage, which stood close to the newly opened Ewell Boy’s School in West Street, was a man called William Smith, a porter with the railway company, and another lodger George Mason, as well as the Spooners’ two young children Ellen and Frederick. It was rumoured later in the many pubs of Ewell that Huggett believed that Lizzie and William Smith were romantically attached.

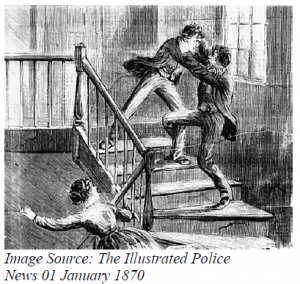

Hiding in the Spooner’s coal house he watched as the lights of the Hop Pole Inn opposite (now the site of John Gale Court) were turned down and waited quietly. At 3.40 am Lizzie rose from her bed to begin to prepare George Spooner’s breakfast as he was due to make a delivery to London early that morning. She went outside to fetch coal to top up the fire she had lit and was shocked to be faced with Huggett sitting on the coals with a bag between his legs. Screaming she ran back into the house followed by Huggett who was shouting that he would kill her and himself. He was also brandishing his knife and tipping gunpowder on to the floor. By this time George Spooner had jumped from his bed and ran down the stairs to restrain Huggett from following Lizzie Richardson who had taken refuge in her bedroom. A struggle ensued and Huggett managed to break free and throw the bag of powder on to the fire. The house exploded demolishing the adjoining wall of the cottage next door and Huggett was blown through it.

Huggett was dead either from the blast or a knife-wound to his heart which had been inflicted with his own weapon. It was possible that George Spooner may have wrestled it from him but he was in no fit state to tell as he had been carried across to the Hop Pole pub with horrendous burns. Witnesses said that his ‘outer skin had come off’. William Smith was also less seriously injured and he was taken to Guy’s Hospital.

The explosion would have rocked the village but would have been no great surprise as accidents emanating from the gunpowder mills were not uncommon. Only six years earlier Ewell resident James Baker had been blown to bits by one such ‘accident’. Messrs Sharp & Co. were moved by the Spooner tragedy to write to the Times not to express sympathy but to assure readers that their premises were not unmanned at nights. George Spooner, 38 years of age, lingered a few days but died from his injuries and a subsequent inquest recorded wilful murder by Thomas Huggett whose own inquest had concluded suicide.

When Thomas O’Brien, the stationmaster at Ewell West station, heard of the incident when he rose on the morning of 22 December he immediately said, “That man I saw last night did it.” He marched across the Gibraltar area to West Street to view the body which still lay in the half-standing house and confirmed that Huggett was indeed the man that had got off the train the previous night. He had to be steadied though when he realised that the lodger that had been taken to Guy’s Hospital (and would later recover from his injuries) was his new employee, porter, William Smith.

© Martin Knight, 2012