The Great Escape – New Unpublished Evidence

A man from Ewell was involved in the Great Escape. He was caught and executed. 80 years to the day of the Great Escape The History Detectorist tells his story.

80 years ago today, on the night of 24 March 1944, more than 200 captured Allied aircrew attempted to escape from Stalag Luft III, a Prisoner of War camp located in an area of Nazi Germany that is now part of Poland.

The attempt was the culmination of many months of careful preparation, including the digging of a narrow tunnel more than 330 feet in length which formed the subject of the 1963 blockbuster movie, “The Great Escape” starring Steve McQueen, James Garner and Richard Attenborough.

Of the 76 Allied prisoners who escaped from Stalag Luft III, 3 managed to get home to the UK and 23 were returned to POW camps.

The other 50 men were murdered in cold blood by the Gestapo. One of those murdered was 106173 Ft/Lt John Francis Williams from Ewell, Surrey who lived with his parents in Stoneleigh Park Road.

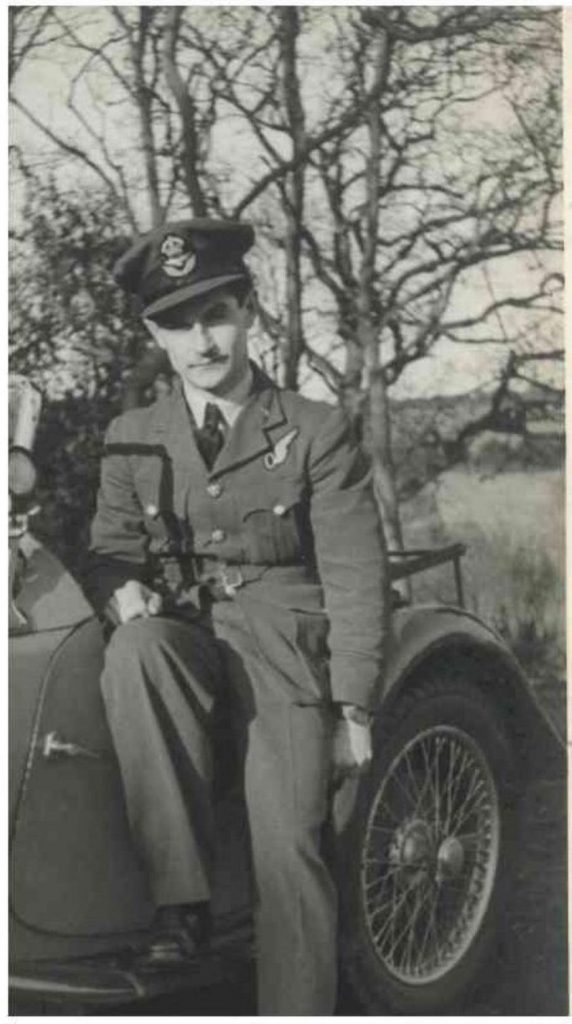

John was only aged 26 years old when he was executed contrary to the Geneva Convention. Prior to the outbreak of World War 2 he had worked for the Milk Marketing Board. He belonged to the Lyric Players in Wimbledon and was keen on photography and driving his blue MG sports car (a photo he took of his girlfriend leaning against his MG sports car is shown below). John volunteered for the RAF and was stationed at Dereham, Prestwick and Rainham.

Disappointed that he did not become a pilot, he instead became an observer on Boston Bombers. He was with 107 Squadron when his Boston III was shot down on 27 April 1942 and upon being captured he was sent to Stalag Luft III.

John’s family were made aware that he was missing on the 4 May 1942, but did not know if he was safe and well until the end of May 1942.

On the 10 June 1942 there was a knock on the door of his girlfriend’s home by a lady looking for her.

The lady had heard a request from John on German radio for anyone listening to the broadcast to contact his girlfriend and to tell her where he could be contacted.

The subsequent correspondence exchanged between John and his girlfriend is not only historically significant, but it also tells the story of an enduring love between a young couple, which with the assistance of Bourne Hall Museum in Ewell, Surrey we would like to give people the opportunity to read about for the first time on this, the 80th anniversary of “The Great Escape”.

In a letter to his girlfriend dated 11 June 1942 John revealed that boredom was an issue, but that he had started to learn German, Spanish and Italian, whilst sunbathing more than he had ever done previously.

John’s letter to his girlfriend confirmed that he shared a hut with 5 other officers and that they all cooked their own food, some of which was supplemented by the contents of Red Cross food parcels.

John did not lose any of his sense of humour and wrote, “Some well-known people in this camp, Wing Commander Bader, Stamford-Tuck, Eyre and me!”

At the time of writing again, John had received 4 letters from his girlfriend and another 3 from family members, but he was only permitted to write 3 letters and 4 postcards in response each month.

In his correspondence, John provides details of camp life and the prisoners’ daily routine. Breakfast was between 9 and 9.30 am, lunch was at 12.30 pm, they had a cup of tea between 1.30 pm and 2 pm, tea at 4 pm, dinner between 7 pm and 8.30 pm and another cup of tea at 11 pm. John added, however, that “It’s not as much as it sounds“ and went on to explain that there were a lot of classes and lectures for him to attend. John missed the everyday things that people often take for granted “like riding on a trolley bus and seeing a film”.

On 7 September 1942, John wrote to his girlfriend and enclosed a photo of himself with one of the other officers he was sharing a hut with. John borrowed a camera from a German officer in order to take the photo.

In the same letter John complained that he had run out of hair oil and had been trying alternatives without success. “I have stopped parting my hair on the side so it now falls in soft waves PHEW!” he wrote.

In many of his letters John asked for photographs to be sent to him and he positioned these on the wall around his bed.

In his letter of 25 September 1942 John informed his girlfriend that the amount of mail he could send home each month had been reduced to 2 letters and 2 postcards. He also told his girlfriend that a fellow prisoner, Ft/O Zakazewski had drawn her using one of her photos. Drawing classes were held and many sketches and drawings exist of the camp.

In his letter of 2 November 1942 John wrote about around 500 officers going over to the sergeant’s compound to see “French Without Tears”, a show written and performed by POWs, which he found entertaining.

There had been quite a lot of snow and a white Christmas was anticipated, but despite only being early November, John wished his girlfriend a happy Christmas in case she did not get to hear for him for a while.

On 13 December 1942, John wrote to his girlfriend telling her that he had received another 29 letters from her and therefore had 147 letters in total which she had sent him. A Red Cross parcel had arrived with a Christmas pudding inside it which they were all looking forward to eating. John was also attending church services and added, “This morning brought forth another of our usual good service and very good padre”.

John confirmed that spirits were high and that they had flooded a football pitch to create an ice rink, on which the Canadian officers could play ice hockey in the afternoons. They had a merry time over Christmas and New Year as they were given 3.5 litres of beer at Christmas and another 1.75 litres for New Year. John had grown a moustache, but shaved it off when it developed twirly ends.

On 29 March 1943, John sent a postcard telling his girlfriend he was due to be moved to another compound within the camp. The camp was becoming overcrowded and had to be enlarged. As the weather was getting warmer and John did not have enough pairs of shorts to wear, he complained about not receiving the right clothes for the right seasons. He had taken up gardening and had planted seeds in order to grow onions, carrots, spinach, and lettuces. The soil in the new compound was much better than in the previous compound John had spent time in and John remarked that there he had only managed to grow one radish.

By June 1943, John was giving elementary German lessons and had grown nine tomato plants which he was very proud of.

John’s girlfriend had been to the dentist so in his letter of 20 July 1943 he wrote that he hoped she “held his hand spiritually” and went on to recount a visit to the dentist in the camp who told him “That he had good teeth for an Englishman”.

John went on to ask for a picture of his girlfriend wearing sunglasses and expressed concern over the fact that she might be called up to serve her country.

John had had an attack of appendicitis and was waiting to find out if he was going to be operated on.

John confirmed in his letter of 20th July 1943 that on 13th September 1942 he had been promoted to Ft/Lt Williams.

On the 24th July 1943, John confirmed that he had had his appendix removed in a nearby French Prisoner of War Camp Hospital and that he was due to spend the next nine weeks recovering.

On 29th September 1943, John wrote in a communication to his girlfriend, “I am sure I shall be holding you in my arms again, looking into your eyes seeing that lovely smile of yours”. His girlfriend had been to the Rembrandt cinema in Ewell, Surrey, which he had fond memories of, and he hoped that they would soon be able to visit the Rembrandt cinema together.

John had seen a production of “George and Margaret” at the camp, “You should have seen the leading ladies,” he wrote. His girlfriend asked whether she should postpone the celebration of her 21st birthday on 13th March the following year until he got home. Initially, he told her not to, but by his next letter on the 24th October 1943, he had changed his mind and expressed a desire for her to do so if she did not mind.

During December 1943, John told his girlfriend about plays and classical concerts that had taken place at the camp and about how the prisoners had built their own theatre. “I wish you could see our theatre, all our own work; it has 350 armchair seats made from tea-type plywood chests in which the Canadian food parcels come,” he wrote. There was also a fad among POWs to design their ideal homes, he explained.

In mid-February 1944, John lovingly wrote, “I’m sure it won’t be long now, my love, before we are together again and then we must endeavour to make up for lost time, mustn’t we? I’m sure you won’t mind me telling you this, but recently I’ve felt a little lonely, my darling, I miss you so very, very much; your letters are a wonderful antidote for the gloom and I love receiving them. I spent yesterday afternoon framing a couple of pictures of you, a very pleasant way to pass time which seems to bring you very close to me.”

John passed on news to his girlfriend from a family friend whose daughter’s husband had been killed in December 1943 while serving in the RAF. The couple had only been married since June 1943, and prior to that, the daughter had been engaged to a merchant shipping captain who was killed when his ship was torpedoed.

John’s final postcard to his girlfriend was written on the same day of the escape and contained the message “I hope to see you soon!”

Sadly, John would never be reunited with his girlfriend and was not able to find a way back home to celebrate her 21st birthday with her as he had planned.

John was last seen alive on the 6th April 1944 before being brutally murdered by the Gestapo under the direct orders of Adolf Hitler and cremated at Breslau.

John is remembered with Honour at Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery in the west of Poland and was mentioned in Despatches.

The notes John’s girlfriend kindly allowed the curators of Bourne Hall Museum in Ewell, Surrey, to make in 2015, when she lent John’s letters and postcards to the museum, also help to keep John’s memory alive because without them it would not have been possible to write this article.

Even with the considerable passage of time, John’s girlfriend never wanted to be parted from his correspondence, so it is a great privilege for us to be able to refer to the historically significant parts of the letters and postcards sent by John from Stalag Luft III.

80 years after The Great Escape, John and his girlfriend’s love story continues in the hearts and minds of the people who read about it, regardless of the country in which they live.

This article is therefore as much about an enduring love as it is about one of the most talked-about events of World War 2.

Top photo: John in his MG sports car.