Housing: What can be done, nationally and locally, to address the affordability crisis?

We hear much about the housing crisis in this country. This is often synonymous with the assertion that we have too few homes. In fact, overall, there is no shortage of homes in the UK – the total number of residences is approximately the same as the number of households who want a home, even taking into account those ‘hidden households’ where, for example, young people want to move out of the family home but cannot afford to do so. However, there are significant issues regarding the cost of housing in some parts of the country, and there are issues with the way that housing is distributed, particularly between the generations.

Housing in places such as Epsom and Ewell is unaffordable for many, particularly the young and key workers in sectors such as health and care. House prices are driven upwards because of the relatively high salaries and other wealth of many in the region and also by the historically low-interest rates that currently prevail. For many, a home is an investment as well as somewhere to live. Residential accommodation in this country is particularly poorly distributed by comparison, say, with many of the countries of continental Europe. It is not in the interests of housebuilders to put sufficient housing on the market that prices will drop – they prefer to hoard land to maintain their share price.

What can be done, nationally and locally, to address the affordability crisis? Much more genuinely affordable housing needs to be provided, including social housing for subsidised rent. A relatively recent study by Herriot-Watt University suggests that we need around 150,000 additional genuinely affordable homes per annum for the next ten years. Not all of these, of course, need to be ‘new build’ – some could come from our existing housing stock, acquired by local authorities and housing associations to meet genuine housing needs.

Second homes and properties left unoccupied for more than a few months should be highly taxed to encourage higher occupancy rates. Fiscal incentives should be available to encourage downsizing, especially given our ageing population, and more housing should be designed for the active and not so active elderly. Authorities such as Epsom and Ewell need to encourage the release of as many brownfield sites as feasible. For example, the potential for mixed uses, including residential, on large car parks and current commercial estates, such as Kiln Lane and Longmead, needs to be investigated. Authorities need to require house building at considerably higher densities than has been achieved in the past, employing high standards of design.

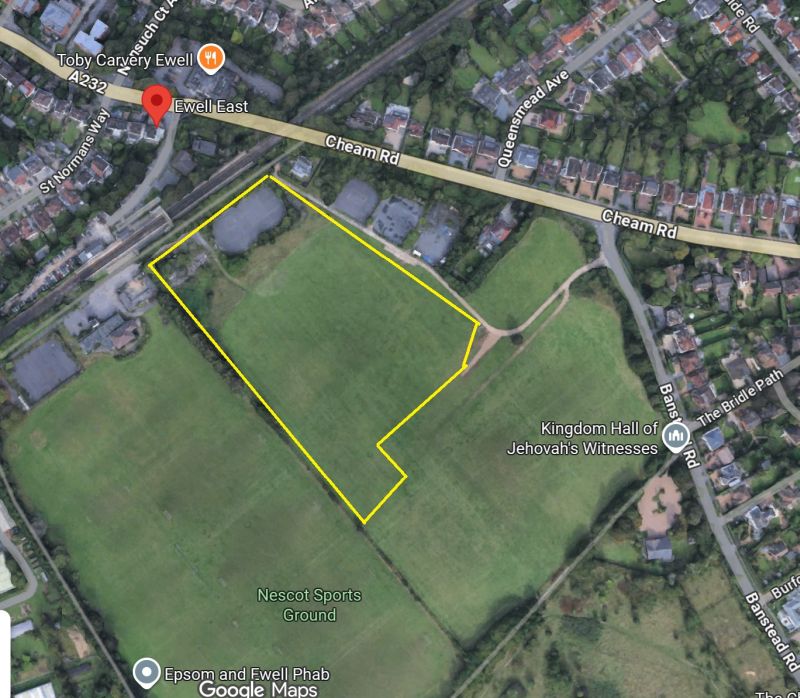

What is not needed is the very high and indeed unrealistic housing targets imposed on local authorities like Epsom and Ewell by the central government. There is no requirement, unfortunately, that most of these homes should be genuinely affordable. Epsom and Ewell have only very limited potential to build new homes on previously developed brownfield sites. Consequently, there is a danger that councillors will see no alternative to losing some of our much valued Green Belt and other countrysides. Be clear, significant areas of Green Belt and other open space in Epsom and Ewell – around Horton and Stamford Green, near Langley Vale, on and close to Priest Hill, and close to The Downs and the College – could be lost forever.